Portraits and Dreams Discussion Guide Background Information

Background Information

BACKGROUND INFORMATION: FRAMING APPALACHIA

In 1975 the young photographer, Wendy Ewald, moved to the Appalachian region of Eastern Kentucky to live and work. She began teaching photography to young middle school students in the community and quickly recognized their creativity and passion for taking pictures. She and her students began to create a series of photographs that later became a critically acclaimed art book, Portraits and Dreams.

Approximately a decade earlier, in April 1964, former President Lyndon B. Johnson had begun his “poverty tours” and declared “an unconditional war on poverty in America” from a porch in Martin County, Kentucky – not far from where Wendy’s classroom would be. As the War on Poverty was being waged, the region was thrust into the national spotlight, in part, due to photographs compiled ina photo essay featured in LIFE magazine – then, the most widely circulated weekly periodical. While LIFE planned for this essay to be an indictment on “a wealthy nation’s indifference” (Catte, 2018), the extreme images of poverty in the region offered little critical context or reflection on the systemic policies and economic practices that created the conditions within which many rural Appalachians were living. Rather, these images reflected what has come to be popular in collective imagination: images of white Appalachian people in poverty. These older representations reflected an absence of Black communities living in the region, and in doing so, failed to situate poverty as a systemic problem impacting racially and ethnically diverse communities in Appalachia(1). Broadly, this wave of media coverage led to a distrust of the media in Appalachia; not wanting to become a national stereotype for poverty, many people in the region wouldn’t allow their pictures to be taken.

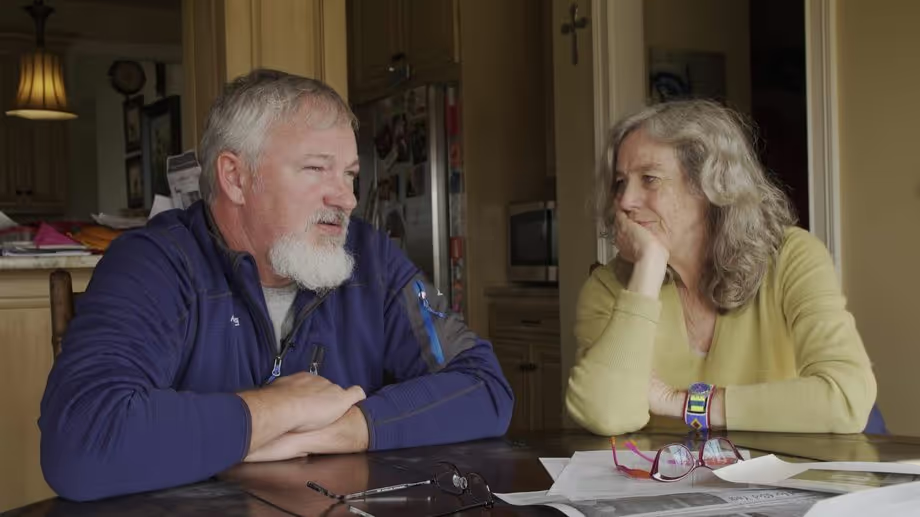

It is interesting, then, to consider the work in Portraits and Dreams within the genre of photography, but as rooted in a more intimate educational and relational setting. In the film, Wendy revisits her former students decades later to reflect on their time together and the photographs they compiled. Her young pupils are now adults working in various fields, facing hardships from divorce to incarceration, and their singular experiences offer insight into historic regional concerns as they reflect on their passion for photography as young people.

This film takes the viewer on a reflective, multi-generational journey in a region that has long faced economic challenges, been impacted by the opioid epidemic, and been subjected to extractive industrial practices. With the community’s economy built around high impact labor, little space is left for young people to explore other fields of interest like the arts, as they navigate the narrow path for what is seen as a successful life in their hometown. While Portraits and Dreams connects former students’ lived experiences to the historic, and sometimes difficult, realities people in the region face, it does so without simplifying narratives of Appalachian life as singularly defined by hardship or constant struggle. In this way, it offers all viewers an opportunity to reflect on how they come to frame and understand the lives of others.

(1)To learn more about Black history, life, and culture in the region, visit Black in Appalachia.

ARTS, CULTURAL ORGANIZING, AND ACTIVISM IN APPALACHIA: A BRIEF HISTORY

With the wave of Appalachian images gaining national press, people in the region began organizing to combat the stereotypes and raise awareness of the systemic oppression and barriers they had experienced for decades. They relied on political and community organizing and creative modes of resistance.

As Wendy worked with her students, another group of young mediamakers were making a name for themselves in Letcher County, Kentucky by documenting the region to tell the more complex narrative of their home. What began in 1969 as a War on Poverty job training initiative to teach filmmaking to disadvantaged youth quickly grew into an independent, nationally-recognized production company known as Appalshop. Appalshop is now a 50-year-old organization, working in arts, film, education, radio, theater, and community archiving. In the 70’s however, Appalshop was in it’s formative years with a team of young people who had a mission to document the region the way they experienced it, first-hand. The work of Portraits and Dreams aligned with their vision of place-based media by putting the power of documentation in the hands of local people.

A few hours south of Letcher County, Kentucky in East Tennessee sits the Highlander Education and Research Center (formerly known as the Highlander Folk School). Highlander’s reputation as a civil rights stronghold has grown over time, and is rooted in Highlander’s central role as a training center for activists involved in labor rights and racial justice movements. As a training ground for Civil Rights activists in the 1960’s it brought leaders like Rosa Parks, Septima Clark, John Lewis, Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph David Abernathy, and many others together to be trained in strategies for community organizing and non-violent resistance strategies, where skills training supported preparation for engaging in actions like the Montgomery Bus Boycotts and sit-ins. Highlander describes its work as a catalyst for grassroots organizing and movement building in Appalachia and the South. Highlander continues working with people fighting for justice, equality, and sustainability, and supporting their efforts to take collective action to shape their own destinies.

EXTRACTIVE ECONOMIES & IMPACTS ON FAMILY LIFE

Central Appalachia has long been known for its coal industry. Many of the towns throughout east Kentucky, where Wendy and her students created their photographs, are named for the companies, CEO’s and Wall Street brokers(2) who created towns which were historically built for the sole purpose of mining coal. Famously, coal companies didn’t pay their employees with actual U.S. currency, but instead gave them what was called “scrip.” Scrip was a company created currency and was only useful in the company stores. As scrip became the unofficial currency of company-owned towns, the possibility for workers to achieve economic stability, to save money, or pay off debts to the company-store were determined by the coal companies themselves. This early example of the systemic parameters that impeded financial stability and economic success for the Appalachian workforce also illuminates the power and impact that coal companies had in shaping individuals’ and communities' lives and futures.

Central Appalachians spent much of the 1900’s struggling with coal companies on various fronts. Deep mining was dangerous and companies were often accused of cutting corners for financial gains, leading to threatening working conditions for the miners. Eventually, mechanization replaced human labor, creating a high rate of unemployment as well as a massive outmigration to more industrialized cities to find jobs. Mechanization also introduced new environmental threats to the region. Strip mining and mountaintop removal mining did away with the need for underground miners, but the practice meant literally removing a mountain and pushing debris down into the valleys and rivers where people lived, in order to access coal. Boulders have crashed through homes, redirected water and manmade coal dams have flooded towns. Through this practice, water sources have been heavily polluted with metal and toxins from the coal(3) and natural environments, as well as wildlife, have been destroyed.

These are some, but certainly not all, of the examples of what Appalachian Americans have been struggling to combat for over a century to secure safe and healthy lives in their own communities. The history of extraction dates back to the first coal barons and industrialists living in the Northeast who held rights to the minerals extracted from the region, and who kept the wealth at the expense of local communities. Many of the mine owners and corporations did not live in the region, though they profited from extractive practices. This reality contributed to an even starker lines of inequality and a persistent distrust of “outsiders” in Appalachia. Due to industry dominance and the intersecting impacts of extractive practices, community resistance emerged in health, environmental, labor, and racial justice movements.

(2)To learn more about the historical influence of place names in Kentucky see Robert M. Rennick’s 1984 book Kentucky Place Names

(3)To learn more about the hazardous impacts of mountaintop removal see the following documentary films in our resource section: Strip Mining in Appalachia (1973) by Gene DuBey;

Strip Mining: Energy, Environment, and Economics (1979) by Frances Morten and Gene DuBey

Buffalo Creek Flood: An Act of Man (1975) by Mimi Pickering; and Sludge (2005) by Robert Salyer

RURAL RESISTANCE: SOLIDARITY AS LEGACY AND INHERITANCE

For a century, people in Appalachia have been resisting and organizing against harmful labor conditions, unfair wages, environmental impacts of extraction, and working in solidarity to refuse stereotypes that minimize the dynamic realities of lives and communities in the region. Legendary labor uprisings - from the 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain to the 1973-74 Brookside Strikes (featured in the 1976 Oscar-winning documentary Harlan County U.S.A.), to the more recent Black Jewel Protests and the 2018 West Virginia teacher strikes, have garnered national attention. The long history of resistance plays out through the songs of the region with the 1932 call to action anthem like “Which Side Are You On?” written by Florence Reece, the songwriter and wife of a United Mine Workers of America organizer. In 1987 filmmaker John Sayles wrote the song, “Fire In The Hole” for the film “Matewan” that is reflective of the songwriting tradition of a rallying cry for laborers. Hazel Dickens recorded the original version of the song, with the lyrics

“Stand up boys, let the bosses know

Turn your buckets over, turn your lanterns low

There's fire in our hearts and fire in our soul

But there ain't gonna be no fire in the hole”

This legacy of resistance is still strong in the region. In the spring of 2017, 150 neo-nazis descended on the small Appalachian community of Pikeville, Kentucky(4). Seeing the hardships and believing in the stereotype that the region is all white and fearful of anyone different, they saw the town as an easy target to organize(5). However, they were met with shuttered doors and local resistance. Whitesburg artist, Lacy Hale, created a block print to express how she and many in her community felt about this rally. The hand carved print showcases rolling hills, trees, and a small cabin with the words “No Hate In My Holler”. The print resonated with so many that she later converted it to a screen print as well. This art piece has now become a new symbol for tolerance and love and has been used in movements to support LGBTQ+ and the Black Lives Matter movements. When asked what inspired this work, Hale said:

“I made this design because I was furious that white supremacists were coming to eastern Kentucky to recruit. Since that protest, it has evolved to represent anti-homophobia, anti-domestic violence, etc. It's so encouraging to see so many people identify with this phrase. I've shipped No Hate items all over the US and the world to holler transplants.”

Hale has distributed this work as prints, tshirts, stickers, and throughout the Covid-19 pandemic as face masks. She uses at least 25% proceeds from this design to donate to central Appalachian non profits working towards equality like the Stay Together Appalachian Youth Project, The Louisville Bail Fund, and Black in Appalachia. To date Hale says she has donated over $5,000.

(4)Estep, Bill. "Hardly peaceful, but no violence as white nationalists, protesters yell in Pikeville." Lexington Herald-Leader. https://www.kentucky.com/news/state/article147594424.html

(5)Beckett, Lois. 30 April 2017. “Neo-Nazis and anti-facist protestors leave Kentucky after standoff” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/apr/30/neo-nazis-anti-fascist-protesters-kentucky-pikeville

POPULAR REPRESENTATIONS OF APPALACHIA

“The kids taught me that it’s less interesting to frame the world only according to my own

perceptions. I had to recognize what they were seeing, and what their vision asked of the

world. What I hoped was that these pictures would have an effect on the lives of the

people who are looking at them. But sometimes one culture or class of people is looking

at another, which can have serious consequences. Because of the viewers’ assumptions,

they can be blind to what they’re looking at. We need to be open to see what’s there.”

- Wendy Ewald, Portraits and Dreams

Appalachia is a complex story, full of contradictions and challenges. However, it’s also full of color, joy, and culture. Representation matters when showcasing any community, and considering the history of representation, this is especially true for Appalachia. Allowing locals, and young children, to quite literally frame their own daily lives through photography meant giving them the power to document their home region on a personal level. Taking a critical approach to framing and representation as a practice continues in the region today, with organizations like Appalshop and their Appalachian Media Institute (AMI). Since 1988, AMI has prepared generations of young people to work in their communities and to confront persistent problems. In learning how to examine and represent local community issues, youth in AMI develop a range of verbal, artistic, and technological skills that connect them civically to their home communities. Each summer AMI pays up to 12 young Appalachians to participate in its Summer Documentary Institute, where they spend 8 weeks learning the history of documentation in the region, discussing their own experiences, and being trained in how to create a short documentary. At the end of each summer the students produce three short documentaries highlighting the culture and issues that are important to them. As an archive, these student-made documentaries have created a 30+ year catalog of what Appalachia looks like through young peoples’ eyes; ranging in topics from LGBTQ+ experiences, environmental justice, and reproductive health rights.

An important part of resistance in Appalachia is continuing to challenge notions of a homogeneous, white culture and community landscapes that were instituted in national imagination with the late 20th century photographic representations of the region. While everyone in the film Portraits and Dreams is white, it is important to complexify whitewashed, popular representations of people living in the region. As is true for the entire nation, Indigenous people lived in the region long before the first European Settlers arrived, and Appalachian life and culture has been shaped, at its roots, by Black and Brown communities who continue to live, work, and grow community in the region today. A prominent example of this is in Harlan County, adjacent to Letcher County - where Portraits and Dreams was filmed - a group that calls itself the East Kentucky Social Club, has organized and maintained relationships with Black coal miners from their community, and with those who have migrated out. Some estimate it to have a membership of 1,500. The club has held large scale reunions all over the country to help preserve their history and relationships to each other and their community.