Wuhan Wuhan Discussion Guide Background Information

Background Information

The First Months of COVID-19

“People were too optimistic about this virus at the start.”

— Wuhan Medical Professional

“This pandemic is unprecedented. We don’t know much. We may make mistakes.”

— Dr. Zheng, ER Doctor, Wuhan No. 5 Hospital

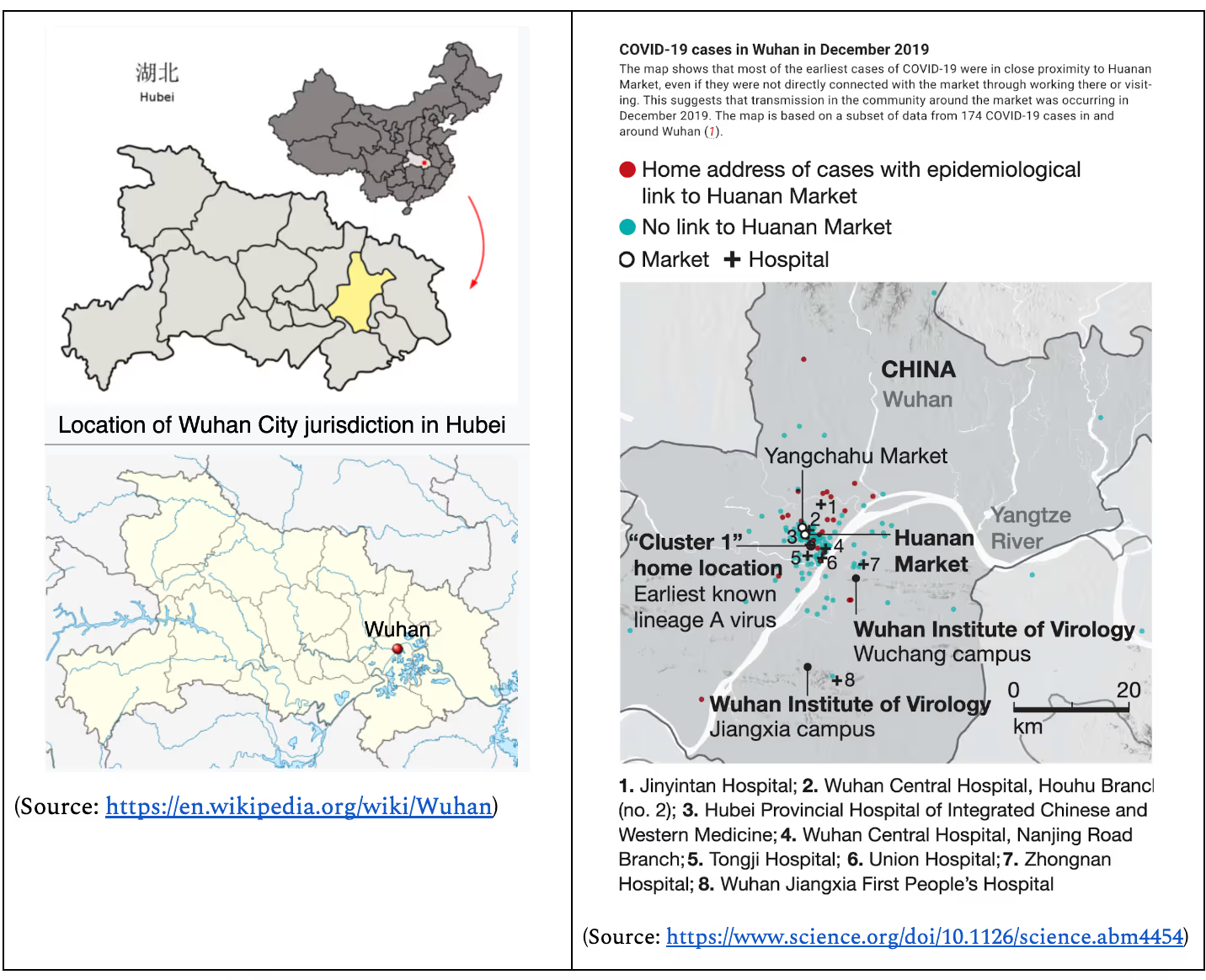

- On December 12, 2019 a cluster of patients in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China reported shortness of breath and fever. Two weeks later, the World Health Organization was notified of a number of cases of pneumonia of unknown origin in Wuhan. Initial clusters of this outbreak were mapped and appear to have originated in the Hunan Seaford Wholesale Market in Wuhan.

- On January 7, 2020 Chinese authorities identified and isolated a new coronavirus as the causative agent of the outbreak. With the Chinese New Year in the coming weeks, Chinese authorities allowed residents of Wuhan to continue moving freely around the city, not fully aware or informed of how contagious this new coronavirus would become.

- On January 23, 2020, China quarantined Wuhan to contain the coronavirus (COVID-19), sealing itself off from the rest of the country for the next six months. The World Health Organization (WHO) had confirmed that this coronavirus was spread by human-to-human contact but a global public health emergency had still not been declared. At this point, it was estimated that the probability of transportation of COVID-19 to other cities in China before lockdown was approximately 369.

- On February 11th, the WHO officially named this novel coronavirus strain as COVID-19.

- By the end of February, Italy alongside China, had become a COVID-19 hotspot and over the course of the next month, the virus spread across the globe.

- Over time, and with extensive research completed and published by a variety of scientists and NGOs, the Hunan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan is confirmed as the most likely place of origin for the virus. Certainly as with any virus, virologists will continue to compile new studies, assemble new data, and continue the important work of sourcing the place of origin for the SARS Co-V-2 will continue.

Wuhan and the Pandemic

Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province situated on the banks of the Yangtze River, is a city of 11 million, a key transport and manufacturing hub, and the place where the coronavirus was first detected. At the end of 2019 a small group of patients were transferred to Jinyintan Hospital—the most qualified hospital in Wuhan to deal with contagious diseases. It appeared they were suffering from pneumonia with fever, cough, and dyspnea (heavy labored breathing.) Their CT scans showed many had large white abnormalities in the lungs, but still nothing other than some sort of pneumonia was identified. More patients began to arrive with similar symptoms and memories of the SARS outbreak 17 years ago began to surface. On December 31, 2019, China sent their National Health Commission to Wuhan and after the working group, and the expert group, conducted many field visits and studies, they also concluded it was some type of viral pneumonia.

The first death from this disease occurred on January 2, 2020. The next day, four elite Chinese medical institutes conducted an unprecedented testing of samples from Jinyintan Hospital. Ten days later this “unknown” pneumonia was named “novel coronavirus pneumonia” — COVID-19. A national press conference was held on January 20th announcing that this disease was transmissible amongst people.

Three days later, Wuhan announced an unprecedented city-wide lockdown sealing itself off from the world and closing all boundaries in and out of the city. We see in Wuhan Wuhan how the city was transformed. Streets and highways usually crowded with people, bicycles, and cars were desolate. Amidst surging cases of the virus, hospital beds became scarce and in response. In response, two new hospitals were hastily built in less than two weeks consisting largely of prefabricated rooms and components. The 1,000-bed Huoshenshan Hospital (meaning Fire God Mountain) opened its doors on February 3, 2020 and five days later, its sister hospital, Leishenshan (meaning Thunder God Mountain), opened with another 1,500 beds. Stadiums were converted and the convention center was turned into a shelter for people needing to isolate or for observation. To staff this surge of cases, medical assistance from around China flew into Wuhan totaling more than 38,000 additional healthcare professionals.

On April 8, 2020 Wuhan lifted its lockdown, 76 days after it began.

Collective Stress and Trauma

“There is going to be severe trauma for our medical workers. It’s a process. But it will get better.”

— Dr. Zheng, ER Doctor, Wuhan No. 5 Hospital

Collective stress and trauma have been common global experiences as a result of the COVID-19 global pandemic. Healthcare workers and frontline caregivers became particularly vulnerable to adverse mental health consequences such as anxiety, depression, insomnia. For professionals in Wuhan, these adverse mental health issues were exacerbated because of the lack of preparation and knowledge of the virus itself along with the ensuing death toll, and disruption of education, employment, daily routines, and family life. “Preparation and anticipation are critical buffers of psychological trauma because feeling prepared reduces the sense of being overwhelmed,” but as the pandemic unfolded, uncertainty increased and these mental health issues accumulated.

The openness of the film participants to share their lives during this unprecedented time offers viewers a rare opportunity to connect with the fears, emotions, and vulnerability of individuals living in the city who were the first to experience a widespread outbreak and lockdown. Throughout the ongoing pandemic, connection itself became a scarce resource, but through the filmmaking process viewers have the opportunity to bear witness to individual challenges that others faced, as they unfolded amidst COVID.

Here are only a handful of scenes that shine a spotlight on the individual and collective traumas of the Wuhanese people:

- There are many who look to Dr. Li Wenliang from Wuhan Central Hospital, the first to send out a warning to fellow clinicians on 30 December 2019, as a hero. In Wuhan Wuhan a scene of a candle-lit altar to his memory is shown. He died on February 7, 2020 of COVID-19.

- In front of Fangcang Temporary Hospital, we meet Psychologist Chang. She is being introduced to 11 volunteer psychologists in front of a former convention center transformed into a makeshift hospital. We listen as Dr. Chang acknowledges their sacrifices and affirms the emotional toll of this work by saying, “we have our own fears and hardships.” She then escorts them to one of the makeshift tents where they each become fully covered in PPE with the only identifying marker being their name written on the outside of their jumpsuit.

- As the group of psychologists delegates which groups needs therapy, one doctor simply states: “You don’t have to ask me. I can tell you this. Everyone here needs therapy, including me.”

- In a very poignant sequence of scenes we see the emotions of ICU Nurse Susu come to the surface. As she gets her hair cut by one of the volunteer hairdressers, suits up and returns to the ICU she shares, “We’re all facing the same challenges. I didn’t want to have any regrets.”

- Dr. Zheng recalls that he and his colleagues were informed that on Lunar New Year’s Eve, his hospital was taking care of over 1000 COVID patients, lined up in the hallways, squeezed in like in a market, waiting six or seven hours for a CT scan or to get an I.V. As he recounts that night being on call, with people in chairs if there were no beds, he says to the camera, “How did this happen? When will the end? I didn’t feel desperate. But I also didn’t see any hope… To an old classmate I said, ‘If I don’t make it, please take care of my child to the best of your ability.’ I’ve told no one this.”

When the film opened in February 2020, Wuhan had been locked down for over a month and the outbreak was at its first peak.

When director Yung Chang “inherited” the raw video material he was immediately drawn to the characters and the humanistic footage. He learned that the 300+ hours of film had been collected by 30 filmmakers who were in Wuhan to gather material ‘’’’’’on the Yangtze River. Within weeks of their arrival, Wuhan was locked down and they were unable to leave. They pivoted quickly, and with incredible access, started to do what they knew how to do: they started filming everyday Wuhanese people, who despite extraordinary circumstances, opened up their lives and told their story to the world.

Chang recalls in an interview at CAAM Fest 2021, “We were just entering our first wave of the virus and the footage I watched was revealing the early experiences of everyday people, frontline workers and healthcare workers in a way that I had not seen before. This wasn't ripped-from-the-headlines, salacious footage — it was intimate, emotional, three-dimensional storytelling.” Chang also shared that this was the first time he was not on the ground filming, but rather from the safety of his home office in Toronto, he found himself looking through the eyes of other cinematographers, stitching together stories, filtering out scenes and creating this unique “time capsule” documenting the first months of COVID in Wuhan, the epicenter of the pandemic.

Of the many noteworthy aspects of Wuhan Wuhan, this documentary and the process of making the film, reflects how connection, collaboration, and collective processing can be creatively discovered amidst difficult times. Whether you were behind or in front of a camera, or engaging in other creative outlets; creative expression offered one outlet where individuals could find a sense of connection despite isolation.